This is an old revision of the document!

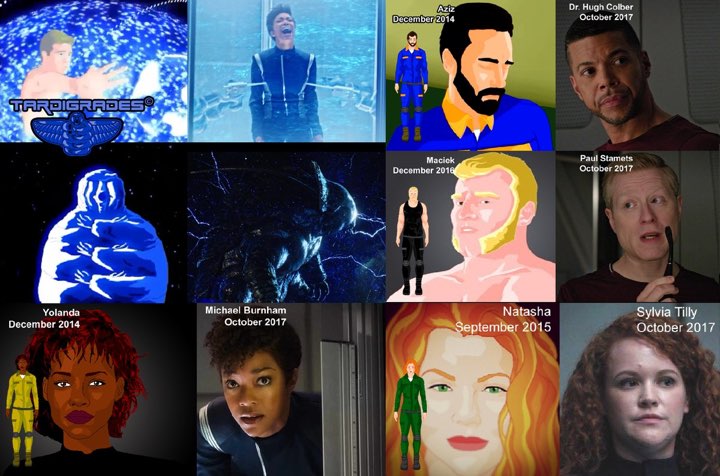

SUPERFICIAL SIMILARITIES? The defense’s grounds for dismissing the copyright lawsuit against Star Trek: Discovery dismiss the similarities between it and the Tardigrades videogame as “generic.”

SUPERFICIAL SIMILARITIES? The defense’s grounds for dismissing the copyright lawsuit against Star Trek: Discovery dismiss the similarities between it and the Tardigrades videogame as “generic.”

Breaking Down the Case for Dismissing the Tardigrades Suit

CBS Lawyer Details Fundamental Flaws in Copyright Infringement Case Against Star Trek: Discovery

Table of Contents

Just what’s wrong with the lawsuit against CBS and Netflix over Star Trek: Discovery, which developer Anas Abdin claims infringes on his unreleased videogame, Tardigrades?

In a December 3, 2018, letter to U.S. District Court Judge Naomi Reice Buchwald, attorney Wook Hwang spelled out precisely why he believed the case shouldn’t move forward: Essentially, that Abdin’s claims that Discovery stole his ideas, and that Netflix (Discovery‘s international distributor) is equally liable, don’t hold up under the law.

Substantially Similar?

Plaintiff’s Response

Lawyers for Anas Abdin submitted a letter to Judge Buchwald December 5, 2018, replying to the grounds for dismissal cited by CBS and Netflix two days before. The reply will be detailed here later today.

At the heart of CBS/Netflix’s defense is the idea that Discovery and Tardigrades, despite some superficial similarities, are not substantially similar — a critical test against which copyright infringement claims must bear up.

What is Substantial Similarity?

According to the American Bar Association, in copyright infringement cases courts traditionally test for substantial similarity using “a subjective, factual analysis called the ‘audience test,’” whose goal is to see if ordinary observers, unless they set out to detect the differences between the works, “would regard their aesthetic appeal as the same.”1)

Moreover, the audience test “asks whether the defendant wrongly copied enough of the plaintiff’s protected expression to cause a reasonable lay observer to immediately detect the similarities between the plaintiff’s expression and the defendant’s work, without any aid or suggestion from others.”2)

Four Remedies for Infringement

Hwang, of the Loeb & Loeb law firm, characterized Abdin’s case arising from the “common use of enlarged, space-based tardigrades and an assortment of other random ‘similarities’ (e.g., a gay male couple),” by asserting four claims of copyright infringement, seeking four separate remedies:

- A permanent injunction against production of Star Trek: Discovery.

- Actual damages resulting from the alleged infringement.

- Statutory damages allowed under U.S. copyright law.

- Attorneys’ fees and costs.

Other Copyright Violations

According to Hwang, Abdin’s suite also alleges violations of the international Berne Convention, an international agreement regarding copyright and the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990 (VARA).

Unprotected Elements

The defense refers to the legal principle that copyright law doesn’t protect an idea, merely a creator’s original and specific expression of an idea. According to Hwang, whatever similar elements exist in both the Tardigrades game and Discovery are different original expressions of what might be common ideas.

For example, Hwang argued, Abdin cannot copyright the idea of tardigrades since they are real creatures that exist in nature, nor can he claim ownership of the idea of human-sized tardigrades in space:

That tardigrades are able to survive unprotected in space is a scientific fact that is not original to (much less exclusively owned by) Plaintiff. Nor can Plaintiff claim ownership of the basic idea of using tardigrades in a fictional space-based story, any more than an author could claim copyright protection over the idea of placing dinosaurs on a fictional island zoo.3)

Only Abdin’s particular visual representation of a tardigrade can be copyrighted; Discovery‘s tardigrade is presented using a very different “aesthetic appeal” (see “What is Substantial Similarity?”).

CBS attorney Wook Hwang criticized Anas Abdin’s ‘bare and speculative allegations’ that any of the defendants had the access to actually copy Abdin’s unreleased videogame. — ‘No Proof of Access’

Human Domino

Abdin’s claim that his adaptation of actual tardigrades cannot be protected by copyright either, Hwang noted, as the idea naturally flowed from the very idea of a tardigrade-based character. Hwang pointed to a relevant case involving Domino’s Pizza human-sized domino character in the 1997 case Ollie v. Domino’s Pizza, Inc., which found that “the humanizing of a domino is an idea not subject to copyright protection.”4)

Trek Tardigrades Predate Videogame

Furthermore, Hwang noted that the notion of tardigrades in Star Trek predated Abdin’s 2014 publication of his game’s concepts, pointing to a 2013 Scientific American article by Kyle Hill, “How Tardigrades Saved the Enterprise,” in which the author opined “that Captain Kirk should have used tardigrades to save U.S.S. Enterprise in … Star Trek Into Darkness).5)

Generic Similarities

Having dispensed with the tardigrade’s lack of copyright protection, Hwang said all that remained of Abdin’s case were “random similarities scattered throughout the works, which cannot support a finding of substantial similarity.”6) Hwang addressed Abdin’s examples of alleged copying:

- A gay relationship.

- Uniforms delineating rank.

- Use of the term “emitter” to describe a light-emitting device.

- Stock character elements, such as:

- A blond white male scientist.

- A darker-complexion homosexual male.

- A female of African descent with messy curly hair.

Example: Copied Costumes?

Among the items listed in the lawsuit as copied by Discovery from Tardigrades are the Trek series’ uniforms. The complaint describes Tardigrades as featuring uniforms depicting characters’ ranks, for example:

“Heretofore, the Star Trek series has not used any uniform styled, or colored in this manner, until plaintiff’s [Tardigrades] was published.” Abdin called the style “a total departure from prior Star Trek uniforms,” and therefore had to have been copied from Tardigrades.7)

Hwang cited several copyright cases in which even more specific similarities than Abdin alleges failed to be found by courts to be protectable:

- Hogan v. DC Comics (1999), which found “a stock character or basic character type … is not entitled to copyright protection,” even including an instance “where two characters had same name and were both half-vampire and half-human, of similar age, and shared other characteristics such as ‘thin-to-medium builds, pale skin, dark messy hair and a slovenly appearance.’ Abdin’s alleged copying goes no further than describing similarly superficial similarities.8)

- Lewinson v. Henry Holt & Co., LLC (2009) rhetorically noted that, “if a stock character such as a drunken old bum were a copyrightable character, so would be a drunken suburban housewife, a gesticulating Frenchman, a fire-breathing dragon, a talking cat, a Prussian officer who wears a monocle and clicks his heels, [and] a masked magician.”9)

No Links to Original Works

Hwang also criticized the lawsuit’s lack of links to works Abdin claimed to have published online, beyond a short treatment attached to the legal complaint. Despite the lack of links or attachment substantiating his claims, Abdin “confusingly defines the allegedly infringed ‘Original Work’ to encompass other materials published on various websites, including Adventure Game Studio Forums, [Abdin’s own] Anas-tronaut Blog, YouTube, Steam Games and Reddit.”10)

Since the legal complaint provided no other means by which CBS/Netflix could determine what other materials posted on those sites might have been infringed upon, Hwang said Abdin did not satisfy “well-settled pleading requirements”; therefore, the case should be dismissed.”11)

No Proof of Access

Crucially, Hwang noted, Abdin failed to demonstrate Discovery‘s creators even knew about Abdin’s game prior to his initial complaint to CBS — such access is a critical part of making a case for copyright infringement.

Hwang criticized Abdin’s “bare and speculative allegations” that any of the Defendants had the access to actually copy Abdin’s work. To establish access Abdin must “plausibly allege either: (1) a particular chain of events or a link from his work to the creators of the allegedly infringing work, or (2) that plaintiff’s work was widely disseminated.”12)

Instead, Abdin offers no such chain of events or link between his game and Discovery‘s development, nor does his postings on various websites constitute wide dissemination, according to the 2008 case, O’Keefe v. Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide, Inc., which established “the mere fact that [a plaintiff’s] work was posted on the internet prior to the creation of defendants’ work is insufficient by itself to demonstrate wide dissemination.”13)

Late Copyright Registration

As for Abdin’s attempt to claim statutory damages of up to $150,000 per instance of infringement plus his cost for legal representation, Hwang argued Abdin registered his copyright with the U.S. Copyright Office in June 2018, months after Discovery premiered in September 2017 — too late to qualify.14)

“Even where the alleged infringement begins before registration and continues after registration, statutory damages and attorney fees are still unavailable,” Hwang cited from the 2016 case, Solid Oak Sketches, LLC v. 2K Games, Inc.

Not Covered Under Berne Convention, Visual Artists' Law

Abdin’s claims under the international copyright agreement, the Berne Convention, and the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA), which recognizes under American law the concept of creators’ lasting moral rights to their work.

Hwang dispensed with both these claims by arguing:

- Abdin’s claim under the international Berne Convention is irrelevant because Berne extends no copyright protection beyond that already offered under U.S. copyright law.15)

- VARA offers no protection to the Tardigrades game, which fails to meet the legal definition of “works of visual art — a narrow class of art defined to include paintings, drawings, prints, sculptures, or photographs produced for exhibition purposes, existing in a single copy or limited edition of 200 copies or fewer.”16) Abdin’s treatment — the only tangible work submitted with his legal complaint — “falls within none of these categories.”17)

Netflix in the Clear

Abdin’s attempt to extract damages from Netflix for its international distribution of Discovery (in the U.S., only CBS All Access carries the show) should fail, Hwang argued, because American copyright law cannot be applied outside the United States.

The only domestic act attributed to Netflix is [according to Abdin] having “entered into a contract in the United States with the CBS defendants.” … But the mere act of licensing allegedly infringing works for foreign use does not constitute copyright infringement. See, e.g., Fun-Damental Too, Ltd. v. Gemmy Indus. Corp (1996), (“mere authorization and approval [in the United States] of copyright infringements taking place outside the United States is not a copyright violation and does not create jurisdiction over those extraterritorial acts”).18)

Answer Due

Abdin’s reply to CBS’ proposed grounds for dismissal were due to the judge by December 6.