Defense, Plaintiffs Rebut Opposition to Summary Judgment

Heavily redacted documents confirm Axanar is broke, plus a new angle on creative consultant David Gerrold

Table of Contents

Main article: Parties in Axanar Case Oppose Summary Judgment

In the last filing before their upcoming hearing in a federal copyright infringement case, attorneys for Axanar and its opponents, CBS and Paramount Pictures, replied to the opposition each had submitted, asking Judge R. Gary Klausner to deny the other's call for summary judgment.

The replies, plus hundreds of pages of exhibits, were filed December 5, 2016, in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles. They made several notable revelations, including confirmation of AxaMonitor‘s report months before that Axanar was broke.

Hitting Back Hard

Each side hit back hard at the other’s recently filed briefs opposing summary judgment as requested by opposing counsel, while shoring up their own call for summary judgment. The plaintiffs’ objective was to demonstrate by evidence that Axanar’s actions constituted copyright infringement, and that the case should be sent to a jury to determine damages.

For the defendants’ part, their goal — in addition to successfully arguing Axanar’s depiction of Star Trek constitutes fair use — was to derail the studios’ attempt to get a partial summary judgment by proving the material facts they alleged remain in dispute and should be decided by a jury.

Plaintiffs' Reply

The studios’ reply brief focused on Axanar’s claims its works were not substantially similar to Star Trek, that any possible infringement was protected by the fair use provisions of copyright law and that no specific evidence could be produced showing monetary damage to the studios by Axanar.

Substantially Similar to Star Trek

Lawyers for CBS and Paramount forcefully rebutted the argument made by defendants Alec Peters and his Axanar Productions that his films, the short Prelude to Axanar, and the planned feature, Axanar, were not substantially similar to the Star Trek owned by the studios:

Defendants’ claim in this case is that they are entitled to create a full-length film featuring copyrighted characters such as Klingons, Vulcans, and Federation officers, along with Star Trek weapons, spaceships, settings, and dialogue – so long as they do not include Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock. This is not the law.1)

Under that theory, however, no work derivative of the original Star Trek series would be entitled to copyright protection, upending well established rights by copyright holders to exclusively create derivate works, Grossman wrote:

What is Substantial Similarity?

What is Substantial Similarity?

According to the American Bar Association, in copyright infringement cases courts traditionally test for substantial similarity using “a subjective, factual analysis called the ‘audience test,’” whose goal is to see if ordinary observers, unless they set out to detect the differences between the works, “would regard their aesthetic appeal as the same.”2)

Moreover, the audience test “asks whether the defendant wrongly copied enough of the plaintiff’s protected expression to cause a reasonable lay observer to immediately detect the similarities between the plaintiff’s expression and the defendant’s work, without any aid or suggestion from others.”3)

Moreover, the audience test “asks whether the defendant wrongly copied enough of the plaintiff’s protected expression to cause a reasonable lay observer to immediately detect the similarities between the plaintiff’s expression and the defendant’s work, without any aid or suggestion from others.”3)

Star Trek: The Next Generation, the second Star Trek television series, takes place in a different time period from The Original Series, and includes different fictional characters. However, there is no question that this series was a derivative work, incorporating the very same elements copied by Defendants (Klingons, Vulcans, spaceships, weapons, language, etc.). Under Defendants’ theory, they (or any other commercial television studio) could have produced that series, and there would be no substantial similarity, and thus no infringement.4)

No Fair Use

Grossman disputed the defense theory that, even if Peters had infringed on the studios’ copyrights, Axanar’s treatment of Star Trek was transformative — adding new meaning to the original work — and therefore protected from copyright claims under copyright law’s fair use provisions.

In her opposition to the plaintiff’s partial summary judgment motion, Axanar attorney Erin Ranahan asserted that Prelude to Axanar‘s documentary-style presentation made it a “mockumentary,” which under a definition in Wikipedia, automatically qualified the short film as a parody.5). Grossman contested that definition:

The Axanar Works are not satire, commentary or parody and, by Defendants’ own admission, were never meant to be anything other than a “professional” and “independent” Star Trek work. Further, no case has ever held that the creation of a non-satirical sequel or prequel is “transformative” and there is no basis for doing so here.6) Defendants also claim that there is no specific evidence of monetary damage from the Axanar Works, but the Supreme Court has clearly held that the creation of unauthorized derivative works, as Defendants have done here, constitutes harm sufficient to preclude application of the fair use defense.7)

Financial Harm

Central to the plaintiffs’ claims of financial harm by Axanar is the idea that the defense’s theory would allow others to create their own competing versions of Star Trek. Grossman wrote:

Competing studios [could] create “professional,” “independent Star Trek films” and television shows, featuring all of these elements. The Copyright Act grants Plaintiffs the “exclusive” right to create derivative works and Defendants’ interpretation of the Copyright Act would destroy the longstanding rights of content owners, allowing infringers like Peters to create sequels, prequels and spinoffs without paying any license fees to the creators of the underlying works.8)

Attempt to Dispute Facts

Attorney David Grossman, writing for the studios, pushed back against the defense’s attempt to create “disputed issues of fact” in its opposition to the plaintiffs’ call for a partial summary judgment.9) A judge can only issue a summary judgment if he decides all the material facts in the case are undisputed. If even one is in dispute, the case must go to trial for a jury to determine the facts.

In its opposition brief, the defense argued, “Because contradictory inferences arise from the facts relating to the question of willfulness, summary judgment on willfulness would be inappropriate.”10)

However, Grossman pointed out in his reply, the plaintiffs were seeking only a partial summary judgment that would allow the case to move to trial for a jury to determine damages. Whether Peters willfully infringed on Star Trek copyrights related only to damages, not whether any infringement had occurred. Grossman wrote:

In an effort to create “disputed issues of fact” Defendants’ Opposition brief raises a number of issues that are not relevant to Plaintiffs’ motion such as whether Peters’ conduct was willful. … These issues, at best, relate to the amount of damages to be awarded after a ruling on liability.11)

Defendants' Reply

The defendants’ brief replying to the plaintiffs’ opposition to Axanar’s call for summary judgment attempted to bolster its claims that:

- The Axanar script had been superseded since the lawsuit was filed and therefore not actionable for infringement.

- No evidence from the plaintiffs disputed the defense claim the Axanar works were substantially similar to Star Trek.

- Axanar’s use of Star Trek intellectual property is protected by fair use.

Premature Adjudication

Central to Ranahan’s theory is the notion that Axanar‘s script — upon which the court rejected her motion to dismiss the case months before — had been superseded by newer versions that plainly placed the planned feature film in the realm of fair use. Of the earlier script, which Peters had publicly announced was “locked,” Ranahan wrote:

While this Court found an allegedly “locked script” sufficient to proceed at the motion to dismiss stage, the undisputed evidence shows that Defendants do not intend to proceed on that script. … There have been several new scripts since then, and other considerations about the style Defendants intend to pursue.12)

All those script alterations, of course, have occurred since the lawsuit was filed in December 2015, and since Peters raised (and spent) $1.4 million on the premise of that “locked” script.

Not Substantially Similar to Star Trek

Since the Axanar works are not a strict copy of Star Trek, determining whether they infringe on its copyright requires an analysis of whether the two are substantially similar. Under such an analysis, Ranahan wrote:

Plaintiffs fail to provide sufficient evidence to show that the works at issue “taken as a whole” are substantially similar. Instead, Plaintiffs argue that Defendants copied disparate “elements” of their alleged works. … Not only is this insufficient as a matter of law to show infringement, but because the “elements” Plaintiffs point to are largely or entirely unprotectable, the Court must “filter out and disregard” them.

Ranahan went on to observe, for example, that Star Trek’s Vulcan species is not sufficiently delineated to qualify as a copyrightable character once unprotectable elements are filtered out, such as pointed ears, men’s bowl-cut hairstyles and their serious and contemplative nature. “None of these characteristics, either alone or in combination, is sufficiently particular to define a distinctive character,” she wrote.13)

Filtering out such supposedly unprotectable elements in order to prevent a finding of substantial similarity has been a feature of defense arguments since its rejected motion to dismiss. At that time, Judge Klausner found:

When viewed in a vacuum, each of these elements may not individually be protectable by copyright. Plaintiffs, however, do not seek to enforce their copyright in each of these elements individually. … The Court finds it unnecessary to analyze whether the allegedly non-protectable elements of the Star Trek Copyrighted Works are eligible for copyright protection because Plaintiff describes these elements in the Complaint solely in an effort to demonstrate how the Axanar Works are substantially similar to the Star Trek Copyrighted Works.14)

Fair Use

Peters’ defense centered on his attorneys’ declaration that the Axanar works are “transformative” — something that alters Star Trek “with new expression, meaning, or message.”15) — and therefore entitled to protection from this lawsuit as fair use of Star Trek’s intellectual property.

Ranahan wrote it’s clear that Axanar provides such new meaning to the “grab-bag of disparate and widely-separated elements that Plaintiffs allege as their ‘work’ in this case,” claiming that case law provides “ample precedent for artistic works that ‘comment’ on other artistic works.”16)

The notion that Prelude, for example, qualifies as commentary, Ranahan asserted, is due to its format as “a ‘fake’ documentary,” or “mockumentary,” whose definition in Wikipedia she declared makes the format inherently a parody and therefore transformative.

Months before, in her motion to dismiss the case, Ranahan used a different definition from an actual dictionary, dictionary.reference.com, for the term mockumentary, which relates to format not content, making no mention of an intrinsic parodical nature: “A ‘mockumentary’ is a movie or television show depicting fictional events but presented as a documentary.”17)

Intent is Irrelevant

The defense theory of the case requires it to find any possible example of commentary it can in Axanar’s works in order to demonstrate how transformative it is — even if that commentary wasn’t originally intended. It only matters how an audience would interpret the film’s commentary on something, Ranahan wrote:

« Plaintiffs fail to show that there exists any “market” for non-commercial fan works like Defendants’. Undisputed evidence shows that Plaintiffs have reaped substantial benefits from precisely the type of fan-created non-commercial work that Axanar exemplifies. » — Axanar attorney Erin Ranahan

It is irrelevant that Defendants may not have explicitly claimed fair use as “parody” or “satire” before Plaintiffs brought suit. What is critical [in assessing transformativeness] is how the work in question appears to the reasonable observer, not simply what an artist might say about a particular piece.18)

The Woman is Comic Relief

In the reply brief Ranahan attempted to point to the character in Prelude, where Captain Sonya Alexander (portrayed by actor Kate Vernon) is referred to by Klingons as “Queen Bitch Whore of the Federation” as an example of Axanar’s “commentary”:

Captain Sonya Alexander (an original character) serves as the comedic relief, presenting a powerful character who provides her commentary about the battle, infused with salty language rarely used by female characters.19)

No Harm

Ranahan goes on to support her claim that Axanar had posed no harm to the market for Star Trek products, and even contributed to its market success:

Plaintiffs fail to show that there exists any “market” for non-commercial fan works like Defendants’; provide no evidence that such works have ever been a source of licensing revenue for Plaintiffs; and provide no evidence that such works have ever interfered with or negatively impacted their ability to license commercial derivative works. To the contrary, the undisputed evidence shows that Plaintiffs have reaped substantial benefits from precisely the type of fan-created non-commercial work that Axanar exemplifies.20)

Accuracy, Not Infringement

Finally, Ranahan took aim at the plaintiffs’ criticism about the amount of Axanar’s elements copied from Star Trek, claiming, ”[Defendants] have taken no more from the original than is required to create their own, highly transformative work.”21)

Ranahan justified Axanar’s concern for accuracy in copying Star Trek elements as “a necessity where one work comments on another,” decrying the effect of the studios’ claims as precluding “not only fan fiction, but parody and countless other protected forms of comment and criticism.”22)

MORE REVELATIONS As we review more of the hundreds of pages of documents filed with the court to support each side’s position in their summary judgment motions, we will post additional notable information.

Revelations

The documents produced to accompany the reply briefs revealed more evidence from both sides in the suit, and gave a preview of arguments likely to play out in court.

The biggest may have been a report from Axanar’s own expert financial witness confirming what we have long reported — that Peters had spent all of Axanar’s money.

Other revelations from the court documents included:

- Mockumentary Format A refutation of a key part of the defense’s fair use argument — that Star Trek had never done anything in a documentary-style format.

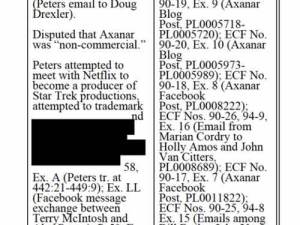

- Netflix, Trademarking ‘Axanar’ Peters’ effort to have Netflix underwrite Star Trek fan productions that would stream on the platform, and his desire to trademark ‘Axanar.’

- Non-Trek Inspiration The defense’s new assertion that Axanar was inspired as much, if not more, by the television shows M*A*S*H and Band of Brothers than by Star Trek.

- Misleading Financials The plaintiffs condemned Peters for trying to mislead the public about his personal expenditures using money raised from Star Trek fans for production of the Axanar feature.

Axanar's Money is Gone

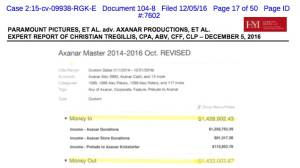

In a report prepared by its expert financial witness, certified public accountant Christian Tregillis, the defense disclosed Axanar had earned $1,428,902.43 from January 2014-October 2016. The same document showed Peters had spent $1,433,003.67 in that same period, incurring a $4,131.24 deficit23) — consistent with overspending previously documented by AxaMonitor’s analysis of Axanar’s 2015 financial report.

See also: Axanar's Thin Financial Report and a New Crowdfund Campaign

Mockumentary Isn't New

The defense had claimed that a documentary-style presentation had never been previously featured in Star Trek, but the plaintiffs disputed that, pointing to the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode, “Trials and Tribble-ations,” a re-telling of Axanar creative consultant David Gerrold‘s original series episode, “The Trouble with Tribbles.” In the re-telling, the plaintiffs argued, “ the primary narrative is exposed through an interview of the main protagonist, interspersed with scenes of the events described.”24)

Netflix and Trademarking 'Axanar'

Email exchanges between Peters and Prelude director Christian Gossett and former chief technologist Terry McIntosh showed Peters had business and marketing plans that included trademarking the name Axanar and approaching Netflix to pay for Axanar to appear on the video streaming giant’s platform.

“Defendants do not dispute that Peters reached out to Netflix for the purpose of distributing the Axanar Works,” the plaintiffs said in a court filing. “Moreover, Peters testified [several lines redacted]. … This is a matter of semantics.”25)

Inspirations for 'Axanar'

In an attempt to distance Axanar from its Star Trek sources, Peters declared in one defense exhibit that Prelude “was inspired by works such as M*A*S*H, Band of Brothers, Babylon 5, The Pacific and The Civil War, all of which were viewed online, and are all publicly available.”26)

However, the plaintiffs noted, Peters made no reference to such inspirations among the materials he provided earlier in response to the studios’ subpoena:

Plaintiffs specifically asked in discovery for Defendants’ source documents used to create the Axanar Works (other than the Star Trek films and television episodes which the parties agreed did not need to be exchanged) and Defendants did not turn over any of these claimed sources.27)

Peters’ declaration to the court seemed to address this complaint, noting:

The memories and experiences of those shows and movies are not something that is tangible [that could be provided according to the subpoena demand], as I rely on my experience and memory when creating fiction works.28)

Peters further disclaimed his reliance on the sourcebook, “The Four Years War,” part of the copyrighted Star Trek Role-Playing Game produced by FASA under license by Paramount Pictures, stating that he made minimal use of it. The plaintiffs discounted that new claim, stating:

Defendants’ argument that The Four Years War was not used as source material ignores, and fails to refute, the testimony of Prelude’s director, Christian Gossett, that Peters used The Four Years War supplement as a “bible,” or the email describing it as such.29)

Misleading Financial Information

In addressing Peters’ spending of donors’ money, the plaintiffs pointed to two different financial summaries he produced in discovery — one of which divulged extensive personal spending from donor money raised to produce Axanar, and a later version in which those expenses were excluded.

See also: Plaintiffs Cite Peters' Shocking Personal Spending in Asking Judge for Summary Judgment

Though defendants’ precise reaction to the two financial summaries was redacted, the remaining text made clear what the plaintiffs thought of Peters’ action:

Peters’ sworn testimony, and the original financial ledger produced in this case, establish the stated fact and Defendants’ cited evidence does not contradict that fact. The evidence shows that [several lines redacted] is irrelevant and an attempt to mislead the court and the public.30)

In earlier court documents, Axanar attorney Ranahan said she would seek to exclude Axanar’s financials from evidence that would be seen by the jury.31)

Redactions

Many of the exhibits included in the court filings featured redactions — blacked out portions of the text — based on the protective order that had been granted for discovery in the case.

However, it became increasingly clear the defense’s many redactions were less about legitimate privacy or proprietary concerns than they were about protecting Peters from public scrutiny of his spending all $1.4 million he had raised from Star Trek fans for a film he never produced.

Judge's Admonishment

Under terms of the protective order governing public release of certain materials deemed confidential by either or both sides, a great deal of the documents filed in support of each summary judgment motion were filed under seal, meaning unredacted versions were filed for consideration by the judge but not fully visible to the public.

« The evidence shows that [several lines redacted] is irrelevant and an attempt [by Peters] to mislead the court and the public. » — Studios’ attorney David Grossman

In approving a recent request to submit documents under seal Judge Klausner warned attorneys that simply relying on the protective order to justify hiding information from the public was insufficient; sufficient explanations detailing why a given document might be redacted must be included in requests to file under seal:

Regarding defendant’s application … the parties are reminded that pursuant to Court’s Revised Standing Order 16, “if a party submits an application to file under seal pursuant to a protective order only, (i.e., no other reason is given), the Court will automatically deny the application if the party designating the material as confidential does not file a declaration.32)

Examples of Redaction

- Repeated citations regarding redacted facts to documents already in the public domain.33)

- Request by defense to file material under seal.34)

- Axanar business plan (redacted).35)

Keywords