REDUCED TO RUBBLE Klingon disruptors cut through a Federation colony, sparking the war that would’ve been depicted in Axanar. (Photo/Prelude to Axanar, Axanar Productions)

REDUCED TO RUBBLE Klingon disruptors cut through a Federation colony, sparking the war that would’ve been depicted in Axanar. (Photo/Prelude to Axanar, Axanar Productions)

The 'Locked' Axanar Screenplay: A Review

The August 2015 Script that Launched a Lawsuit

Editor’s Note: This review by writer-producer Jody Wheeler is based on the August 2015 script producer Alec Peters described as the “fully revised and locked” Axanar screenplay. AxaMonitor obtained the 105-page script from a source who provided it on condition of anonymity.

This version was specifically referred to in the copyright infringement lawsuit filed against Axanar Productions and Peters himself by Star Trek’s copyright holders, CBS Studios and Paramount Pictures.

For this article, Wheeler compared the August 2015 screenplay with several earlier drafts also obtained by AxaMonitor. His review of a much earlier draft was published on March 3, 2016, by 1701News.com, a Star Trek news website. Readers should be aware that significant plot points are discussed in the review.

Review

By Jody Wheeler

AxaMonitor contributor

September 12, 2016

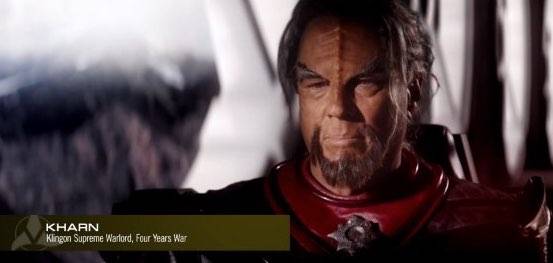

IT’S KHARN’s story now?

That’s the first thing that leapt out at me in reading the “locked” version of the Axanar screenplay producer Alec Peters posted about on August 15 of last year.

See also: Meet the Daily Blogger Critiquing Leaked 'Axanar' Script

A heavy revision of the 2014 script by Peters and former director Christian Gossett, this newer version by Peters and film writer/commercial video producer Bill Hunt addresses the earlier script’s problems of hollow characters, uninspired dialogue, and weak plotting by pulling focus away from Garth of Izar, giving more lines and scenes to other characters, and creating the only real emotional conflict in the story between the antagonist, the Klingon Kharn the Undying, and his lieutenant, Chang.

And by adding a 30 page-long final space battle in the last act. (But more of that in a minute.)

‘Not Terrible’

As before, the Axanar script isn’t terrible. It’s not the best Star Trek script ever, despite director Robert Meyer Burnett‘s boast. Though there’s much that’s new in this script, it’s far from a Page One rewrite. In stretching the script from 95 to 105 pages, it’s more that this script knocked out an exterior wall or two, built on a new room, and added some new furniture in the remaining and otherwise furnished rooms. The general shape is still the same, though you can look around and see some new stuff, which works or not depending on your taste.

THE BIGGEST change here is the shift of focus away from the weakest element in the earlier script — Garth. A perfectly dull and untextured hero, Garth remained the same at the end of the earlier version of the script as he was at the start: Perfect. No personal loss. No personal change. That’s still the case here.

« It’s not Garth’s story of how he won at Axanar. It’s Kharn’s story of how he loses. »

Yes, this is still ostensibly Garth’s story of his victory at the Battle of Axanar. But it’s not Garth’s story of how he won at Axanar. It’s Kharn’s story of how he loses. He’s the only character in the entire movie who really changes over the course of the movie. His choices drive the story forward. It’s on his head that that the fate of the galaxy rests when a final action is required.

That would be a pretty fantastic rewrite of the piece, but for the fact Kharn gets less screen time than Garth. The film keeps telling you Garth is driving this story — but depicts Kharn making all the choices that move the plot towards its conclusion. Kharn acts. Garth reacts.

‘Great Opponents, Small Potatoes’

While Kharn and Garth — presented as two great opponents — do interact, it’s small potatoes. If you expect something like The Wrath of Khan‘s Khan or Nemesis’ Shinzon with their constant face-offs, traps, verbal sparring, action and counteraction, hero and villain vexing each other, that’s not really the case here. (Nor, for that matter, in the earlier-ready-to-shoot script.)

Kharn is challenged more by his lieutenant, Chang, than he is by Garth. Instead of two near-perfectly matched leaders fighting with greater assets for higher stakes, Kharn is mostly sidelined so Garth can destroy the enemy-of-the-scene, with Kharn not even remotely manipulating events. “He tasks me. He tasks me, and I shall have him!”1) does not happen in any way, at any time, in this script.

WHAT DOES happen in this new script are expanded beats for characters introduced in Prelude to Axanar, like Sonya Alexander, Frank Travis and Admiral Ramirez. (Slightly surprising, as Tony Todd, the actor identified with that role, left the production and there were no reported plans to recast.) [Editor’s note: Todd was still attached to Axanar at the time this script was drafted; he departed a couple weeks later.]

While still essentially extended cameos for fan favorite actors Kate Vernon and J.G. Hertzler, these characters now have a bit more to do than before, including a pretty funny interrogation bit for Vernon’s Captain Alexander. That said, these as well as the other new “cameo captains” — one each Vulcan, Tellarite and Andorian — are still essentially interchangeable Starfleet figureheads, all doing the same thing in the story: Providing a familiar face to cut to when orders are issued. A bit of a waste, really.

Talky

Two last notes to wrap this up. Part of that expanded page count comes from inserting a great deal more dialogue into the story. Long and extended bouts of dialogue, filled more with “telling the story” than actually showing it. Best example of this? The Vulcan Scene. Shot and released last year as a teaser to attract hundreds of thousands more dollars for the budget, this scene was a walk-and-talk — two characters telling us what’s going on behind the scenes in Vulcan and galactic politics, floating ominous foreshadowing about the fate of the galaxy, and editorializing about the greatness of humans.

That type of scene recurs throughout the script, enacted by Klingons, Federation, Vulcans — you name it. In many cases, it’s even expanded with Trek-talk technobable, which is fine if you like that sort of thing. In small doses it’s great. When it replaces conflict or characterization, it’s just … long.

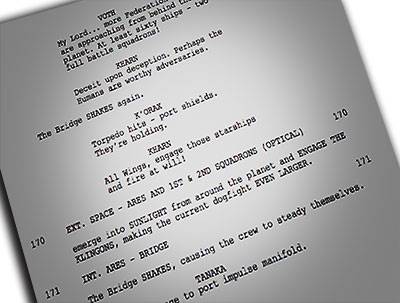

As far as dialogue in that and other scenes goes, if you think, “Deceit upon deception. Perhaps the humans are worthy adversaries,” is crackling good prose, then there’s a borg’s smorgas of lines here. If you don’t, then you’ll tune out. Especially when you get such lines and technobabble in the same exchange.

WHICH BRINGS us to the last bit. The long final act is a putatively climactic space battle between everyone — thirty pages of it. That translates to roughly 30 on-screen minutes of space battle. Thirty minutes of wave after wave of starships bashing, blowing and bowling through each other. Thirty minutes of decoy drones, shuttle-interceptors, captains barking orders, and a sea of secondaries announcing shield strength percentages.

Would You Like it?

Each side has its own moment of a “surprise” fleet dropping out of warp to join the battle. The Enterprise (still) shows up to get her licks in. Don’t just imagine typical pew-pew! space battle porn, though. Think bang-bang space battle orgy porn. It’s J.J. Abrams-style scenes on steroids. While I’m quite certain those effects excellently depict that final battle, there’s ultimately not much to it other than a lot of explosions.

Scripts are blueprints for movies. What’s in the script is what’ll appear on the screen. What’s in this script is okay, though it has still far too many problems for my tastes. For yours? Without reading the script, is there any way to know what the final movie might be like? Actually, I think there is. Two minutes of Axanar exist, minutes pulled from this script. A brief but telling example of the dialogue, storytelling style, pacing, effects, even director choices — the Vulcan Scene.

Watch

BEST PREDICTOR of whether you’d have enjoyed the Axanar movie? What did you think of the Vulcan Scene?

Alongside the ship battles from the preview trailers, for the most part, it’s all right there. If you’ve seen Axanar’s Vulcan Scene, you’ve seen the movie in truncated form. How you feel about the scene is most likely how you’d have felt about the final flick.

Given that the final film is incredibly unlikely to ever be made, that’s the closest anyone will ever get to seeing Axanar.

Keywords