Analysis

The Shoe is on the Other Foot

Following Lawsuit, Axanar Ironically Claims Copyright Protection From Fan Edit of ‘Prelude’

Table of Contents

By Carlos Pedraza

AxaMonitor Editor

Main article: Fan-Edit of 'Prelude' Eliminates Alec Peters

After an anonymous fan of Prelude to Axanar posted his version of the short, unauthorized Star Trek film on February 15, 2017 — edited to tighten the story and replacing Alec Peters’ appearance — Peters moved swiftly to have YouTube take it down.

That action, normally straightforward on YouTube, instead opened up a myriad of questions surrounding the legal standing of a production that itself just avoided an infringement verdict, going on to claim copyright protection for its own unauthorized work.

Settlement Terms

The terms of the January 20 settlement between Peters and the two studios suing him for copyright infringement, CBS and Paramount Pictures, allowed Prelude, produced in 2014, to remain on YouTube so long as it was not monetized.

So far as the settlement terms are publicly known, granting permission was a concession that did not automatically invest Prelude with a copyright they could defend in court.

Indeed, Axanar agreed in the settlement to abide by the Star Trek fan film guidelines.

‘While Axanar may hold some kind of copyright even without registration it can’t defend against infringement of any element of its work without violating the fan film guidelines.’ — Legal Standing

No Copyright Registration

The ninth guideline plainly states:

“Creators of fan productions must not seek to register their works, nor any elements of the works, under copyright or trademark law.”

A valid takedown notice submitted to YouTube would require to be the copyright holder of Prelude, something that is far from legally certain.

Axanar Reaction to Fan Edit

In the meantime, as the entity that originally uploaded Prelude to YouTube, Axanar was sufficiently empowered to issue the takedown, and took advantage of that the day Prelude: Redux was posted.

Following the takedown, YouTube’s public notice said, “This video is no longer available due to a copyright claim by Axanar Productions, Inc. Sorry about that.”

WHAT IS THE DMCA?

WHAT IS THE DMCA?

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1996 was a revision of U.S. copyright law since the advent of the internet. Under its “safe harbor” provision websites like YouTube that host potentially infringing user-generated content are safe from legal action by copyright holders if they agree to take down infringing videos upon request. Learn more about this controversial law from this excellent article at Plagiarism Today.

Contacted soon after the fan edit was posted, Axanar spokesman Mike Bawden told AxaMonitor pursuing a fan edit would move Axanar’s focus away from its ostensible goal — producing Axanar as a short film to partially fulfill its obligations to the donors who forked over the $1.4 million Peters completely spent by the past year:

Quite honestly, I’m encouraging everyone to move along and continue with the planning required to produce the two fifteen-minute segments we’re allowed to produce to tell the story of Axanar, so I can’t say anyone is going to do anything about this.1)

Peters’ takedown appeared to go against the advice of Bawden, his public relations director. Following the takedown, AxaMonitor asked Bawden whether the action went against Axanar’s agreement to abide by the guidelines.

Bawden did not respond.

See also: Where to Watch 'Prelude to Axanar: Redux'

Since the takedown, others tried re-posting Prelude: Redux on YouTube. Each one received a takedown notice. The version posted by Australia’s TrekZone.org remained online at its own website, away from YouTube’s policy and the U.S. copyright law, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), under which Axanar issued the takedowns.

History of Fan Edits

Axanar, which often touts itself as a representative of fandom, appeared unaware of the long tradition of fan edits of much-loved (or maligned) films.

Before the term “fan edit” was coined, many “alternate versions” of films edited by other fans or professional editors were simply known as a “cut.” In the late 1970s, many alternate “cuts” of films were released in the United States, and foreign films (such as those from Europe or Japan) deemed unsuitable for American audiences underwent further alterations, score changes and re-titlings. Also fan translation (fandubs or fansubs) of anime is similar in spirit to fan edits.2)

Admittedly, the legal status of fan edits is unclear under copyright law. Fan editors claim fair use (just as Axanar did to justify making Prelude in the first place) because a fan edit “removes, reorders, or adds material in order to create a new interpretation of the source material,” — the same transformativeness argument used by Axanar.

Can Axanar Claim 'Prelude' Copyright?

Studios like CBS, Paramount, Lucasfilm and Disney have a clear copyright for their works. By contrast Axanar’s unclear copyright of Prelude may impair its attempt to defend the film from such things as fan edits. According to Atlanta attorney Michael K. Stewart:

Axanar does have a copyright in this film, at least in the original elements that they contributed. Even though it may be an unauthorized derivative work, the creator of the unauthorized derivative work still owns the copyright in it — even though the overall work may be infringing and he doesn’t gain any rights into the pre-existing material he incorporated into the work. The myth that if you create an unauthorized derivative work, the copyright in that work is automatically owned by the party whose you infringed is just that — a myth.

And while Guideline No. 9 prohibits Axanar from registering a copyright for Prelude, that doesn’t mean Peters had no copyright, Stewart added:

Under the law, you can have a perfectly valid copyright without registering it. Registering it is especially problematic for the studios because not only does it put the claim of copyright on record, but it is a prerequisite to filing a copyright infringement lawsuit.

But without the registration, how could Axanar defend Prelude in court? Some legal observers argue that the case of Anderson v. Stallone (1989) holds that Axanar has no defensible copyright interest in its film.

The Anderson Case

The Anderson case was a copyright infringement lawsuit against Sylvester Stallone, MGM, and other parties over a script for Stallone’s film Rocky IV. This script written by Timothy Anderson was unsolicited and unauthorized, a key fact that led to a decision in favor of Stallone, et al., in federal court.

It was strikingly clear to the Court that Anderson’s work was a derivative work; that under 17 U.S.C. section 106(2) derivative works are the exclusive privilege of the copyright holder (Stallone, in this case); and that since Anderson’s work is unauthorized, no part of it can be given protection.3)

« This is consequently a higher stakes game … because the rightsholder does not have a cheap and fast way to keep the video down, short of suing you. » — Electronic Frontier Foundation

Stewart called Anderson, which was ultimately settled pending appeal, an “outlier case that, to my knowledge has not been followed. … I am aware of no other case where the fact that the work was an unauthorized derivative work deprived the entire work of any and all protection.” That position appeared to agree with the U.S. Copyright Office’s take:

In any case where a copyrighted work is used without the permission of the copyright owner, copyright protection will not extend to any part of the work in which such material has been used unlawfully.4)

The Copyright Office then goes on to note that the creation of the unauthorized derivative work may nonetheless be an infringement.

Murky Issue

Stewart called the protectability “a murky issue,” given possibly contradictory notions in Anderson, the copyright statute itself, and legislative comments on the statute (which are not binding as law but courts often use them to interpret the statute) using a different standard, turning on whether the underlying work was used “lawfully”, not where it was “authorized”.

When based on the “lawful” standard, “the creator of the derivative work would appear to own the copyright in his original portions even if the work was completely unauthorized,” Stewart observed. “Lawfulness, for example, could be satisfied by a finding of fair use.”

Takedowns Failed Before

Axanar has not been successful with earlier efforts to take down videos it didn’t want the public to see: It tried to takedown its "Vulcan Scene" and criticized trailers that were posted on YouTube and Facebook. Axanar pulled the Vulcan Scene from public view shortly after the copyright infringement lawsuit was filed against it. After the Vulcan Scene was re-posted on YouTube, Axanar issued a takedown notice that was successfully challenged.

He concluded, “The law is really, really unclear on this point.”

Legal Standing

It is clear, however, that copyright registration is a prerequisite to defending copyrights in court. So then how could Axanar pursue a takedown to its logical conclusion — a lawsuit defending its copyright under the DMCA — if the guidelines by which Peters agreed to abide preclude registration? So while Axanar may hold some kind of copyright even without registration it can’t defend against infringement of any element of its work without controverting Guideline No. 9.

Challenging the Takedown

If Axanar is indeed precluded from defending its copyright in court because of its settlement agreement to adhere to the guidelines, the fan editor of Prelude — and anyone else posting the Redux — has a case under the DMCA for challenging Axanar’s takedown notice.

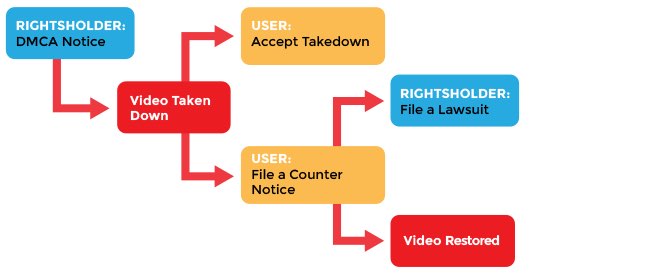

Filing a Counter-Notice

According to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, people who have had content taken down can submit a “counter-notice,” a statement under penalty of perjury that the “material was removed or disabled as a result of a mistake or misidentification,” and consenting to the jurisdiction of the poster’s local federal court in case the rightsholder decides to sue.5)

Two-Week Ticking Clock

The fan editor and other posters of Prelude: Redux told AxaMonitor they have filed counter-notices, giving Axanar only two weeks to file a copyright infringement lawsuit against them. If Axanar did not, YouTube can restore the video. If Axanar elected to sue, Redux would remain removed until the lawsuit is resolved.6)

“This is consequently a higher stakes game … because the rightsholder does not have a cheap and fast way to keep the video down, short of suing you,” the EFF noted.

Can Axanar Sue?

Therefore, if Guideline No. 9’s prohibition against registering for copyright indeed applied to Prelude, then Axanar would be barred from suing for copyright infringement and the video would be eligible for posting once more on YouTube.

It remained to be seen whether CBS or Paramount planned to take any action with regard to Axanar’s copyright claim over Prelude, or whether the claim violates the settlement, of which most terms remain private by mutual consent of the plaintiffs and defendants.

Fair Use Analysis

As it turned out for Axanar in its lawsuit, a federal judge rejected its argument that Prelude made fair use of Star Trek copyrights. How well would Prelude: Redux fare under the same kind of analysis? The EFF sums up that analysis under the following questions,7) each followed by the fan editor’s likely stance.

Is the video transformative? Is it non-commercial?

The fan editor would say yes to first under the theory that his cut comments on the original work and transforms it into a new interpretation. Posted for free on YouTube, and free of any surrounding commercial endeavors based on the work — which severely weakened Axanar’s own case — Redux would likely be found non-commercial.

Is the video a substitute for the original? Would people still want to buy the original after seeing the video?

Axanar could certainly argue the intent of the fan edit is precisely to substitute for the original. But Axanar is prohibited under the settlement from ever selling copies of Prelude, therefore there is no market in which to substitute. The fan editor could, however, do a better job of identifying Redux with the body of the fan edit as clearly not the original Prelude, rather than just in the description of the work.

How much of the original work did the fan editor take, both quantitatively and qualitatively?

Redux would not fare so well under this examination since it uses nearly all of the original work, shaving off four minutes from Prelude, and adding a small amount of additional material.

Was the purpose of his use non-commercial, educational, for the purpose of research?

Already established as non-commercial, Redux‘s editor could make a case that he undertook the project purely as an educational exercise, to comment upon the original and to encourage others to learn through the comparison of the two versions.

If the fan editor’s use were to become widespread, would it harm the market for or value of the original work?

Since Axanar had already agreed never to monetize Prelude the film has no economic or market value likely to be affected this or any other fan edit.

COMMENTS

Discuss this article in AxaMonitor's Facebook group.

Keywords